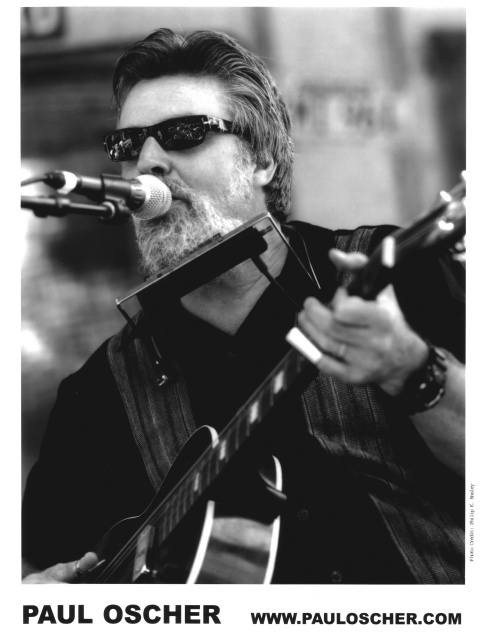

Paul Oscher, legendary, award-winning blues singer, songwriter, recording artist and multi-instrumentalist, has recorded over 24 tracks with Muddy Waters as well as dozens with other musicians. Oscher plays unadulterated, down-in-the-alley, gutbucket blues on harp, piano and guitar. “He plays the soul I feel,” said Muddy Waters. (Oscher was the first white musician ever to become a full-time member of a major black blues band—that of Muddy Waters). Oscher writes and plays his own music, and when he does play a blues classic, he puts his own stamp on it. “I always keep that lowdown and lonesome feelin' I learned in Muddy Waters' band,” says Oscher. “I like to keep it real and in the moment.”

Q: Did your parents encourage you to pursue music?

A: My father thought I should learn the accordion because it can sound like any instrument. He said, ‘If you learn that you’ll never want for a job.’ You want to know what the definition of an optimist is? An accordion player with a beeper. Don’t get me wrong—I really like Cajun accordion and Clifton Chenier and I even recorded a Mississippi John Hurt song with me playing the accordion.

Q: When you were 12, your uncle gave you a Marine Band harmonica. Was your uncle a musician?

A: Yes, he played barrelhouse-style stride piano, but not blues. He put me on the musical path when he gave me that harp.

Q: Jimmy Johnson, a southern medicine show harp player who was passing by, taught you the rudiments of blues harmonica. How did that happen?

A: I had a job after school delivering groceries to old folks by bicycle, for tips. You could buy a slice of pizza and a Coke for a quarter. I was waiting out side the store for someone to ask for a delivery and I was trying to learn the harp. I was playing Red River Valley from the pamphlet that came with the harp. This black guy with a processed hairdo and gold teeth came out of the grocery store and said, “Hey kid let me see that whistle you got.” I said, “it's not a whistle it’s a harmonica.” I handed him the harp and he played Wah wah wah wah blues with great tone. The sounds coming from that little instrument blew my mind. Then he played a shuffle and tap danced with it and turned the harp around like a clock still playing it. He was gonna play it with his nose but I stopped him. At that moment I knew I had to learn what he was doing. He showed me how to choke the harp and bend the 4th hole. That’s when I fell in love with the blues harmonica. About thirty-five years later, I figured out the clock trick and I do it in my show sometimes.

Q: How did you get so good so fast that by the time you were 15, you’d hooked up with guitarist/singer Little Jimmy Mae and began playing professionally?

A: I played all the time, night and day, complete obsession and a love for the blues. I used to practice in the bathroom for the echo sound of the tiles.

Q: How did you meet Jimmy Mae?

A: I was walking past this club called the Nite Cap and I was playing my harp—I’d gotten pretty good. A guy in the doorway said, “Hey kid, why don’t you come in here and play that harp for the people?” I looked in the club: it was all black people. The men looked like Ike Turner with pompadour hairdos and the women looked like the Supremes. The guy in the door was the MC named Smiling Pretty Eddie. He was sharp and like every one else, dressed up. There were Cadillacs double parked outside the club. A lot of players (hustlers) hung out there because Eddie used to be a pimp. He walked me to the bandstand and gave me this Elvis type mic to blow out of and it was a Bogen PA system and sounded great. I played “Juke” and “Sad Hours” and when I finished, Pretty Eddie said, “How about it ladies and gentleman? Put your hands together for the little blue-eyed soul brother!” The crowd went wild. I walked towards the bathroom and there was a pretty shake dancer with a long black wig putting pasties on her breasts. One breast was exposed and she was working on the other one. She looked up at me, batted her false eyelashes and said “Hi baby,” with the sweetest most sensual southern black drawl—I was hooked—this was gonna be my life, I liked everything about it, I knew it.

The club became my hangout, Jimmy Mae was the band leader and I’d sit in whenever I could. When the record “Scratch My Back” by Slim Harpo came out, I could play it just like the record. Jimmy and I would perform in a lot of black clubs in NYC. He could sing Little Walter and BB King and we would get over like fat rats. They called us “Salt and Pepper.”

Q: In what city were these black clubs, the Baby Grand, The 521 Cub, Seville Lounge, the Night Cap?

They were in Brooklyn. There were also clubs on Long Island: The Bluebird Lounge, St James Hotel, The Showplace, Club Haven, Community Bar, Club Ruby—there were a lot places where southern black people gathered and appreciated the blues. We played all of them.

Q: In the mid-1960s, you met Muddy Waters back stage at the Apollo Theatre. What were you doing backstage?

A: Jimmy Mae knew the guys in Muddy’s band and we went to meet the band. This was a great blues show with Jimmy Reed, John Lee Hooker, Lightning Hopkins, Bobby Bland, T-bone Walker and Muddy Waters. I wasn’t performing, but I was playing the harp at the back staircase. Muddy heard me playing. We hung with the band after the show at the Theresa hotel and he heard me some more and took my phone number.

Q: In 1967, when Muddy came to New York without a harp player, you sat in with the band, playing “Baby Please Don’t Go” and “Blow Wind Blow.” How did you get to sit in with the band?

A: Luther “Georgia Boy Snake” Johnson called me and told me to come down. Big Walter was supposed to make the trip but didn’t show up at Muddy’s house when they left Chicago. I sat in with the band and after I played those songs Muddy asked me if I could travel. Hell yeah! I met them the next day at the hotel and got in the Volkswagen bus.

Otis Spann was sitting there with his wife Lucille across from him. Drummer S.P. Leary was across from me and Muddy’s driver and valet, Bo was at the wheel. Muddy, Snake and Sammy were in a station wagon in front of us. Spann said to Lucille, “Give me my shit,” and she took a 22 automatic out of her bra and handed it to Spann. Spann checked it and put it in his pocket then asked S.P. if he had a taste. S.P. handed Span a pint of Gordon’s Gin, we all took a swig then handed it up to Bo. Bo took a long swallow and shouted out “I see the moon and the moon sees me, God bless the moon and God bless me,” and we started to move out. I said to myself, boy I’m in it now! The real deal—I couldn’t be happier.

Q: It says somewhere in Muddy’s bio that when he first heard you, he described it as “Paul playing with Little Walter’s amplified sound.” But you were playing acoustically! Do you remember Muddy saying it?

A: I don’t remember Muddy saying that but that was the sound I had tried to get acoustically — very loud and fat tone.

Q: When you were playing with Muddy and the band, were you allowed to play what you wanted or did Muddy tell you what to play and how to play it?

A: Muddy never told you what to play but if I played something he didn’t like, he would cut his eyes at you and scratch his head and you'd know you f—ked up.

Q: Did Muddy want you to play like James Cotton?

A: Yeah, Cotton or Little Walter. And he wanted Cotton to play like Walter until Cotton finally told him he could only play like Cotton.

Q: What were the most important things you learned from the musicians in Muddy’s band, Muddy included?

A: Tone, time and phrasing. And how to be me. One time I was playing a Little Walter part on a song and I messed it up and I said to Sammy Lawhorn, “Wow I sure messed up that Walter solo,” and Sammy said “No you didn’t, you was just playing Paul.” I thought about it and I never tried to play anybody’s solo note for note after that.

Q: Who would you say taught you the most about deep blues phrasing and timing?

A: Otis Spann. He'd sit down with me at the piano till I got it right.

Q: You lived in Muddy’s house on the south side of Chicago with Otis Spann, who taught you piano. How did that happen?

A: We both shared the basement. I had one room and Spann and his wife had the other. The piano was in the middle room. Spann would play it all the time and Lucille would sing. I never tried to play any licks exactly like Spann, but I know his time and phrasing. I taught myself the piano. I first started by trying to play guitar and harp licks on the piano. Then Spann showed me a little simple left hand stuff.

Q: And you learned guitar simply by looking over the shoulders of Muddy and Sammy Lawhorn?

A: Pretty much. Of course I was good enough on guitar when I started with Muddy to recognize what they were doing.

Q: At the end of 1971, after five years, you left Muddy’s band to form Brooklyn Slim?

A: Brooklyn Slim wasn’t a band—it was a name I was using. I got the idea from a bar on Rogers Avenue called “Brooklyn & Slim.” There was a neon sign and the “&” was broken so it just read Brooklyn Slim. I thought, “that’s me, it should be my bar” (Muddy sometimes called me Brooklyn Slim), and it would be a good name to use. I was playing in a bunch of no-name clubs and I didn’t want to associate “big name” Paul Oscher with those kinds of gigs.

Q: What kind of music did you play?

A: I never played anything but blues, but I had a bass player named Chris Wright. He used to sing gospel with The Swan Silvertones and Brooklyn All Stars. He could sing anything from Bobby Bland to Al Green. I also also had a female vocalist named Rose Melody and she could sing any thing, so I played whatever they were doing, soul music or blues. Rose could never say “harmonica.” She’d always say “Paul when you gonna blow your mahonica?”

Q: In 1976, you toured Europe with Louisiana Red, played with your own band in the New York area, and backed up Big Joe Turner, Doc Pomus, Victoria Spivey, Big Walter Horton and Johnny Copeland. What did you learn from that?

A: The more you play with different musicians the more you learn. I’m living in Austin now and have a quartet here; it’s a steady gig but my sidemen play behind lots of other artists and different styles of music. That’s the way it is here. We’ve got some really great blues players here: Mike Keller (guitar with the Thunderbirds) plays with my band when he’s not on the road and Jay Moeller. Kim [Wilson]'s drummer plays with me on different occasions.

Q: When did you develop your singing chops?

A: One night Chris Wright didn’t show up. The singer couldn’t make the gig. We were playing at Lucky’s Fabulous Marble Lounge in Bayside, Queens, a black club. I started singing and nobody broke for the door or booed so then I kept singing at least a few songs every night after that. This girl Deborah left me—then I really started singing and writing blues. She broke my heart.

Q: You are writing a book now about your blues experiences, Alone with the Blues. When do you expect to be finished?

A: My ex wife, a writer, is coming up with a plan. When that book is finished you’re gonna love it. I’m sorry I can’t answer all of your questions in depth, because I am saving those details for the book

Q: In May, 2001, you were scheduled to play at an upcoming blues festival and decided you should play solo. After that solo performance, what happened?

A: The audience loved the show, and I sold 65 CDs, and that’s when I made the choice to play solo. I’m still doing my solo show on the road but I play with a band locally. The solo show helps the band gigs cause all they have to do is listen to my records. I also play a few numbers alone with the band.

Q: Your harp playing has extraordinary tone. How do you get your tone?

A: Good sex! George Smith used to say drink milk (LOL).

Q: You play diatonic, chromatic, and bass harp. Which of the three kinds is most difficult and why?

A: Bass harmonica takes a lot of wind and there’s a large space to navigate. It’s all blow notes. You can't breath through the harp and the reeds are unpredictable. They can choke on you if you blow too hard or too soft. I think diatonic is the hardest to play because you have to make all your notes and every harp is like a different level reed.

Q: You play chromatic in a rack while playing guitar, another unique move. Is that as difficult as it seems?

A: The only difficult thing about that is the rack: it’s so big you can’t see where you're at on the guitar when you look at the fret board. I used to fumble trying to find the guitar pickup switch and volume controls, but I just had them moved to the top of the guitar like a Les Paul—that works great.

Q: You’ve been seen in gigs using a looping pedal to layer harmonica sounds over each other

A: No, I’ve never done that! If I use a loop, its just a 12-bar bass pattern on the guitar to play guitar and harp over. I lay down the pattern in front of the audience so they see exactly what I’m doing and I have a safety switch next to the loop pedal so I don’t trigger accidentally during another part of the show; but sometimes when I lay down a track I forget to turn that loop pedal switch on and I go through playing the twelve-bar pattern and nothing happens—no loop; that’s usually cause for a laugh. I laugh about alot things that sometimes go wrong. For instance, I was playing an electric piano in Springfield, Illinois in a festival and in the middle of my blues solo, I hit the wrong button and the piano started to play Beethoven's “Fur Elyse.” It was a demo tract built into the piano—it was really a riot and the audience laughed too.

Another time, when I got the wireless for my neck rack and guitar, I started walking out in the crowd. I was playing at Turning Point in Pierpont, NY, and I walked off the stage into the audience with the intention of walking around the building and coming in through the back door while still playing—like Guitar Slim did with a long cord. I asked the guy at the front if the back door was open and he said, “I think so.” I told him, “Please open it,” so I walk out the front and around the building still playing and I get to the back and there’s four doors and ain’t none of them open. Three Mexicans in the kitchen see me through the window. They’re saying “cool man, cool man,” and talkin’ about what I’m playing, so eventually they get the idea to let me in the kitchen. I walk through the kitchen and I’m in another place altogether, a fancy Mexican restaurant on top of the Turning Point. I nod good night to the surprised Maitre D' and walk back into the Turning Point through the same door I left—not a very exciting finale for my show. People just asked, “Where’d you go?”

Q: You have said, “The real gift of talent is not the ability to be able to play, it is the gift of the love you have for the music.”

A: That’s what takes you over the hurdles.

Q: Do you ever get nervous on stage or feel you’re giving a bad performance?

A: I always get nervous but I found that if get to the gig closer to start time, I’m less nervous because I have less time to think about what could go wrong. I’ve found that you really need to stay in the zone when you’re playing and not observe yourself while in the zone. Once that happens, you leave the zone; for instance, sometimes I surprise myself as I’m playing and say to myself “Damn that was cool,” well it’s downhill after that. Your concentration was broken by your ego.

I never drink before I play and that really helps you keep your edge. The only time I feel as though I did a bad performance is when the audience doesn’t react to certain solos that always have worked. I’ve found that the cause is not so much my fault, but the fault of the sound engineer. When you see poker faces on an audience after a great solo, it’s because they’re not hearing what you are hearing on stage.

It’s always good to have your roadie in the crowd with a second set of ears to make sure the sound on stage is getting to the people. You can have a great sound in the monitors, but nothing happening in the house. You need to be particularly courteous to sound guys. Sometimes if they have never heard of Little Walter or Chicago blues, they don’t have a clue what the harp is supposed to sound

like in the mix. They pay much more attention to guitar, bass

and drums.

Q: Does any of your equipment date back to your time in Muddy’s band?

A: Yes, I have a road case that was given to me by Muddy and it was bigger then my attaché case I’d been using for my harps. It’s 20in x14in x 9in. I might sell it if a get a big enough offer. I also have a guitar that was given to me by Muddy, but I’m not selling that anytime soon. I needed a bigger case to hold a Hohner 36 melodica and my harps and mic. Muddy liked that melodica — he called it a piano harp and I recorded with it through a Leslie speaker; it sounds just like a Hammond B3. By the way, I was the first to use melodica in the blues.

Q: Do you do any special tunings on your harps?

A: NO. Now speaking about special harps you should know that the low F harp was my idea. Andy Paskas was a tech for Hohner and I asked Andy to make me a low F harp from a Marine Band G harp. I wanted this because Muddy sang “Hootchie Coochie Man” in F sometimes and I wanted play it in first position like I did when he sang in A or G. I played the low F for Mr. Hohner himself at the Hicksville factory and he liked it and didn’t realize a harp that low could be played that well; so about a year later they came out with the low F harp and then later other low harps followed. I never got credit or money for that idea.

Q: You have played “Sugar Mama” in concerts playing two different harps, alternating between a diatonic played through a section of PVC pipe which serves as the wah-wah and a mute along with a larger chromatic. How do you do that?

A: I don’t remember doing that with Sugar Mama but I did do that with an instrumental called “Alone with the Blues” on my album of the same name. That piece was in C and I used a C 64 chromatic and a Bb super chromatic and a low F harp, Melodica and bass harp. It was funny in the studio because the helper had to hand me the Melodica and the bass harp when I needed them. The harmonicas, I could switch with no problem. The track was recorded live.

Q: Did you have to learn how to develop your amazing breath control or did that come naturally?

A: I think you should never consciously think about breath control, just let it happen naturally. It will automatically adjust to what

you want to play, just like you would automatically take a deep breath after swimming underwater. You don’t say, “I’m gonna take a deep breath,” it just happens naturally. But things that help with tone are: first, get a clear vision of the tone you want, and second, play long notes. Don’t cut the notes off too short. Music can be like writing and leaving words out. Long tones also develop your wind. That’s what I’ve heard trumpet and sax players say, but I never really tried to practice like that. The way I practiced was to keep playing the same thing until I got it the way I wanted it—

that worked for me. I never played scales or exercises, etc. I always worked on something I wanted to use.

Q: Do you practice anymore? If so, how and what?

A: I got a gig every week so that’s my practice. When I go on the road, I get more practice. The best practice you can get is playing before an audience. I do, however, try to figure out new ideas and that’s like practicing too.

Q: Is your sense of rhythm innate? Can one learn a sense of rhythm?

A: I think you can learn anything, but it’s like drawing: some people can draw naturally and some can’t.

Q:When you were learning to play blues, some harp players wouldn’t share their Iicks. How did you learn your licks?

A: From records; but you had to put a penny or nickel on the needle to slow it down. You can watch a guitar player and you can see what he’s doing, but you can’t see what a harp player’s doing; it’s all in his mouth. James Cotton told me that when he wanted to see how Little Walter got that warble sound—if he was shaking the harp or shaking his head, something that could be observed—Little Walter would turn his back on Cotton and say, “That’s easy; it’s like this,” and play it, but Cotton couldn’t see what he was doing.

Q: What would be the best piece of advice you would give to someone learning to play the harmonica?

A: Listen to great blues harp players, practice and hang with musicians that are better than you. And always keep a harp in your pocket.

Q: How do you make an intermediate player better? What is the best piece of advice you can give them?

A: Try to get your sound in your head and keep fighting that harp until you’ve got it the way you like it.

Q: What advice do you have for advanced players? What’s the most important thing for them to learn?

A: Don’t try to play better than your peers—just try to play better than yourself.

Q: What has music done for you?

A: It’s made me young when I’m old. I never grew up and I always loved music, so I never worked a day in my life. It was all pleasure. And it got me a whole bunch of beautiful women to get the blues about.

Paul Oscher's website: http://www.pauloscher.com/